For a long time, the idea of culture has been central to the average African’s perception of identity, of decency and of belonging. Today, it has essentially boiled down to the general idea that if one is not adhering to the strict and inhibiting ideals of ‘African culture’, then one cannot be a true African, or that one is buying into Western ideals. This idea gives room to a number of questions.

What even is African culture? Why should it be an impediment to our progress? Why, if it preaches tolerance and unity, is it projected as being inherently at odds with anything foreign?

It is generally understood that culture is a way of life. Based on this understanding of the word, it would be inept to narrowly categorise the lives of more than 1, 4 billion people, spanning across 54 countries and speaking more than 1500 different languages, into an ‘African culture’. Research has shown that Zimbabwe, with up to 70 different ethnic groups and 16 official languages, still cannot boast a singular ‘Zimbabwean culture’, let alone an African one. While this article is not about statistics, it would be prudent to enter this discussion bearing in mind that the idea of a clear-cut, set-in-stone ‘African culture’ is just but a fallacy.

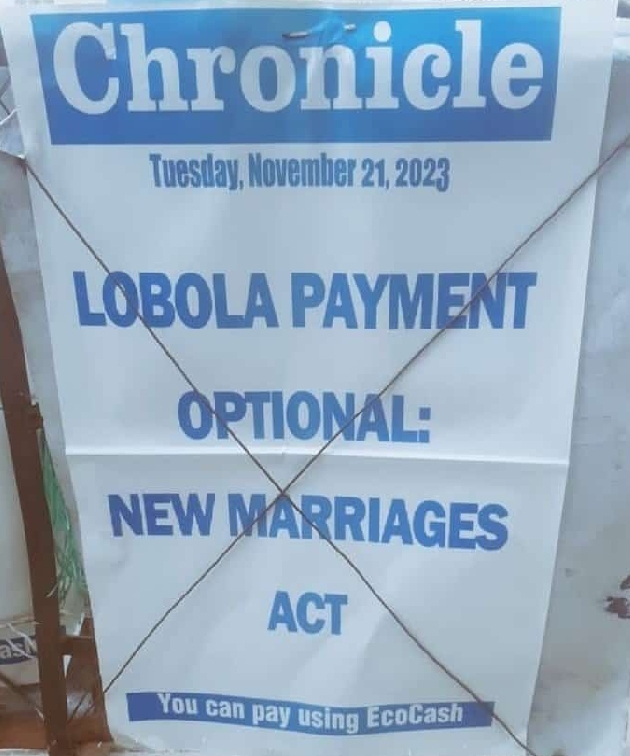

This opinion piece was sparked by a number of tweets made by Zimbabweans, following the amendment of the country’s Civil Marriages Act, under which the payment of bride price (lobola/ roora) was made optional. This means that Zimbabwean legislature no longer mandates the payment that is customarily made by the groom to his father in-law.

While this move may be viewed as being progressive, as it could help in upholding the dignity of Zimbabwean women, it has been met with overwhelmingly negative reactions from a number of people, including women. One Twitter user, echoing the thoughts of many traditional leaders, posted:

You can change the law, but we will not change our culture in any case👍

@MeloC26 via Twitter

This sentiment brings us back to what culture means for people in Zimbabwe. It should be acknowledged that the idea of culture needing to resist change is myopic at best. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has given that culture does not make people as much as people make culture. Culture is a tool that is meant to benefit its people and not the other way around. It has been suggested that,

To remain stagnant and unmoved in a culture or belief is unAfrican. African culture was something our ancestors created based on addressing their immediate needs

Home Team History, via YouTube

Chukwuebuka Ibeh has further buttressed this fact, stating that,

What a lot of people today posit as being indigenous African values are in fact, not indigenous at all and some of what today is resisted as a colonial import did have traces in precolonial Africa.

TedX, via YouTube

In addition to the above, it can be highlighted that maize, a staple in Zimbabwean households today, is not an indigenous crop, but a Western import. Historians have pointed out that while the crop was introduced to inhabitants of the Zimbabwean plateau from as early as 1450 A.D, it did not become a staple until much later in the 19th century. The change and integration that is illustrated by this aspect of Zimbabwean cultural cuisine only goes to to prove that culture, as we know it, is dynamic and not static. Thus, the idea that we must not be open to cultural change is incorrect and holds no weight when subjected to enough scrutiny.

The institution of lobola possesses a number of weaknesses.

For starters, it reduces the bride to an object, a curio that is being traded from the possession of its father to the next male owner, the husband. While a number of people may reject this fact, it is made abundantly clear by their attitudes towards the practice. Many women who support it may be heard saying, “Of course I want to get married properly. Why would I want a man to take me for free? Ndichienderei mahara?”. What this sentiment succeeds in doing is that it exposes the extent to which Zimbabwean women are objectified, such that they now wear their objectification like a badge of honour. The fact that women view the act of being traded for cattle as an achievement, only goes to show that they have been conditioned to accept and embrace their objectification.

Secondly, it is highly manipulative. It is sugar-coated as a form of appreciating one’s wife, when it is not. If it were, then why would it not be paid to the wife herself? Besides, when has appreciation for something ever been forced? The beauty of appreciation is in its spontaneity. The system of bride price has therefore been used by many as a tool to acquire exorbitant amounts of money from their sons in law, at a time when that money is needed the most, to start a family.

Thirdly, it is a hallmark of hypocrisy. It is a system that is laced with double standards. It is often argued that the parents of the bride deserve compensation for raising the bride into a well-rounded, ‘cultured’ and thoughtful woman. In fact, formally educated women often fetch higher sums of lobola. But all of this begs a series of poignant questions: Are men not also raised by their parents? Do grown men simply fall from the sky and look for women to mate with? Although that would be a pretty fun concept for a dystopian novel, it does not reflect reality. In a country with women who clamour for gender equality, this double standard seems to pop up a lot when women try to explain why they ‘should not be given away for free’. Therein lies the hypocrisy.

Fourthly, it ushers in a number of marital problems. It is a system that perpetuates rigid gender roles and limits the scope of flexibility within marriages. Men are known to abuse their wives when they are disappointed by their service, saying, ‘I paid lobola for you, therefore you should make me KFC dunked wings with a side of fries and a mountain dew from scratch, like a proper African woman’. (I really hope this article finds the right audience💀). Women are also known to be trapped in marriages by their own family members, being told to endure pain and abuse, because the husband paid lobola, especially in rural areas.

To be fair, I could write a whole dissertation highlighting the weakness of the system, but I shall keep my argument brief and move on to the last part of this conversation.

Why would such a system prevail, despite its various shortcomings?

Marriage is still a big deal in Zimbabwe and Africa, in general. Marriage and the customs associated with it have thus survived and still exist today. John S Mbiti has put it across saying that, when one does not marry, one rejects society and society will reject him in return, as marriage is customarily a communal rather than an individual affair in Africa. Married persons are also accorded greater respect than unmarried ones.

Ibeh has explained why many Africans seem to hold on dearly to what we perceive as being our traditions, pointing out that,

Because Africa is a continent with a history of having our affairs dictated by outsiders through colonialism and neo-colonialism, it is easy to understand why we tend to cling dearly to what we believe in. I sometimes think of it as a trauma response, a defiance, if you please. We consider our values to be the only thing that is truly up to us to decide.

TedX, via YouTube

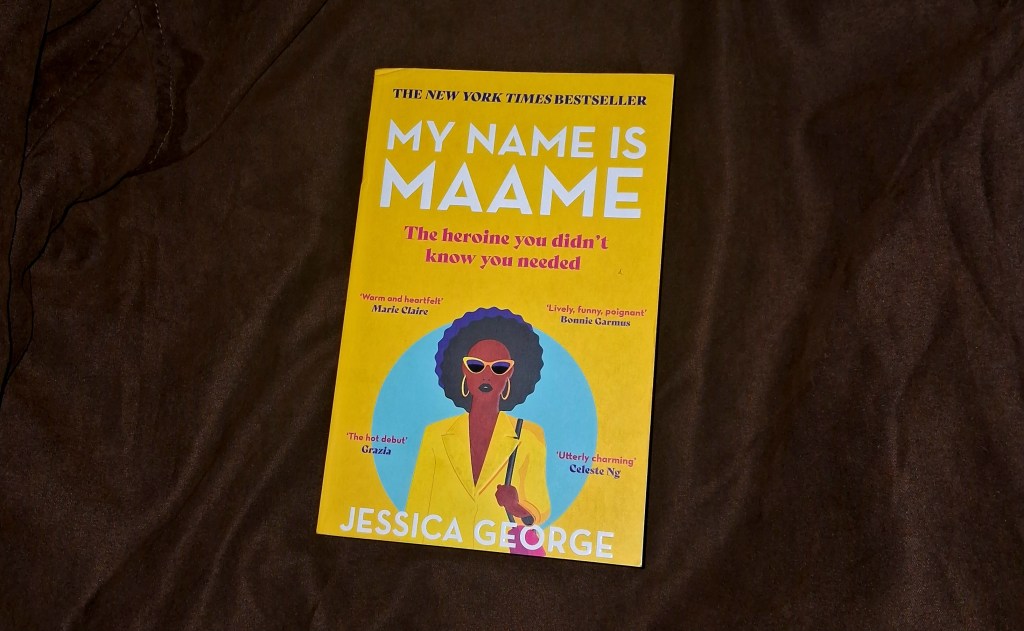

I hope that someday in Africa, it will not be perceived as being radical, to advocate for the full dignity of women. Advocating for human rights is not radical. It is to be human. It is to have a heart, to speak against injustice. It is to extend compassion.

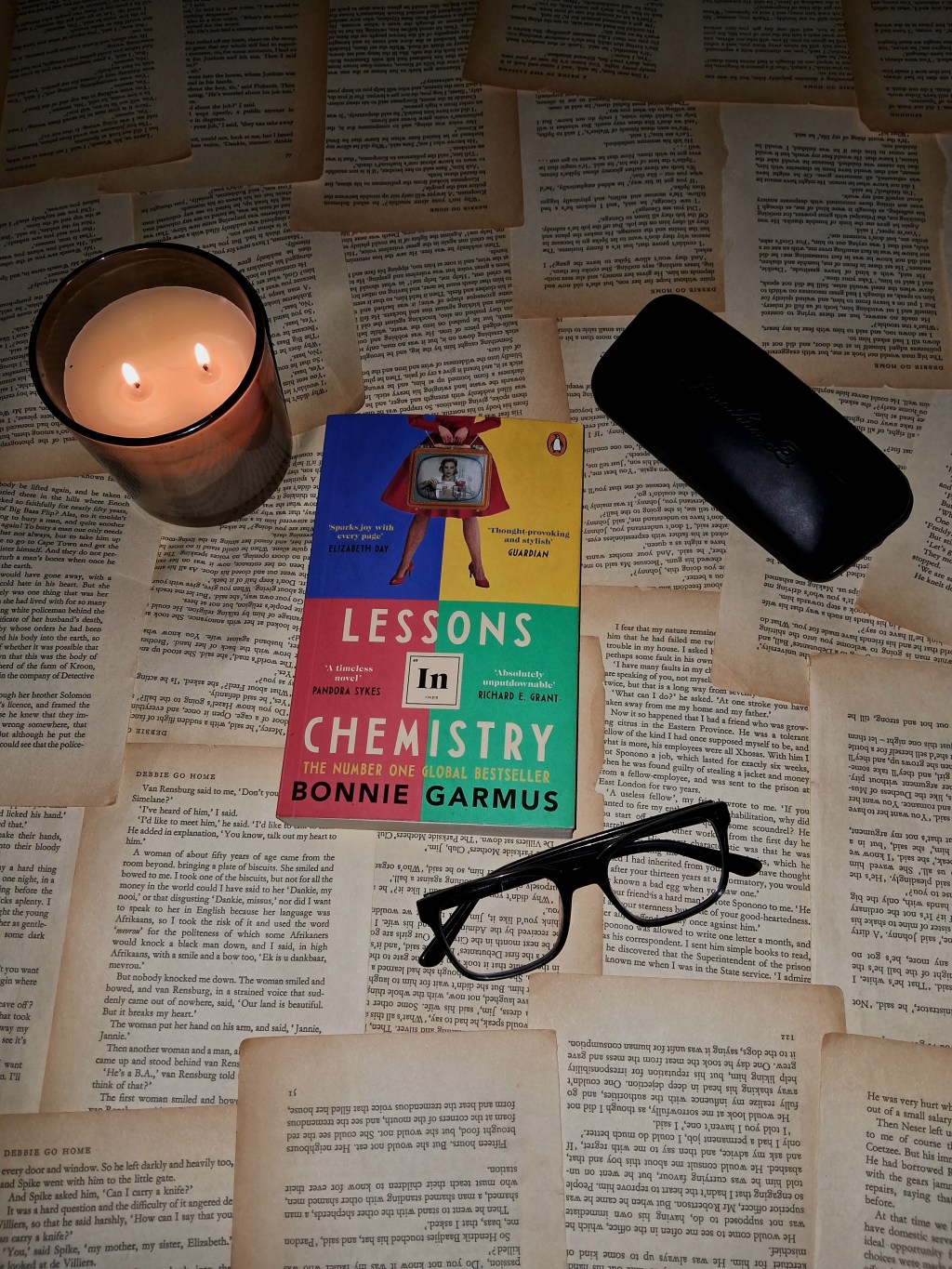

In conclusion, the aim of this article is not to demonize indigenous traditions. It is merely to show that for us to progress as a society, as a nation, and as a continent, we need to be open to change. In the words of Sia Kate Furler, we need to have the courage to change. While it helps to be wary of the possible downsides of accepting certain changes, allow me to leave this question: of what use are our values, if they exist as tools of oppression and marginalisation? (C. Ibeh, TedX)

Follow me on all the socials🥴👍Instagram:https://instagram.com/its_august_ine?igshid=MzMyNGUyNmU2YQ==

@its_august_ine on Twitter and Instagram

Leave a reply to What Makes a Man? “Men of The South” book review – By Augustine Cancel reply