“I feigned sleep until my mother left for school, but even my eyelids didn’t shut out the light. They hung the raw, red screen of their tiny vessels in front of me like a wound. I crawled between the mattress and the padded bedstead and let the mattress fall across me like a tombstone. It felt dark and safe under there, but the mattress was not heavy enough.

It needed about a ton more weight to make me sleep.”

The Bell Jar, p118.

Synopsis

Working as an intern for a New York fashion magazine in the summer of 1953, Esther Greenwood is on the brink of her future. Yet she is also on the edge of a darkness that makes her world increasingly unreal. The Bell Jar draws the reader into Esther’s psychological unravelling, which leads to suicidal ideation, failed psychiatric treatment, and eventual institutionalisation. Through more compassionate care, Esther begins a fragile recovery, though the novel ends with a suffocating uncertainty that makes it a haunting American classic.

Introduction

The Bell Jar, published a few weeks before Sylvia Plath ended her life in a gas oven, is her only novel. It is lauded as an American classic and is considered a feminist text, chiefly because of its exploration of gender norms and personal turmoil from the eyes of a young woman. Her confessional writing style was seen as a return to the dazzling, life–affirming yet death–haunted lyricism of Keats, often dubbed a “Keatsian sense of sweetness and death.” To that end, this review focuses on death, mental illness and racism in the novel.

What if life isn’t always the answer?

“We’ll act as if all this were a bad dream.”

A bad dream.

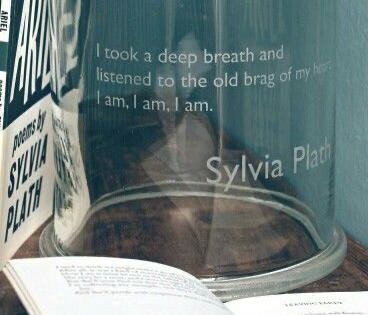

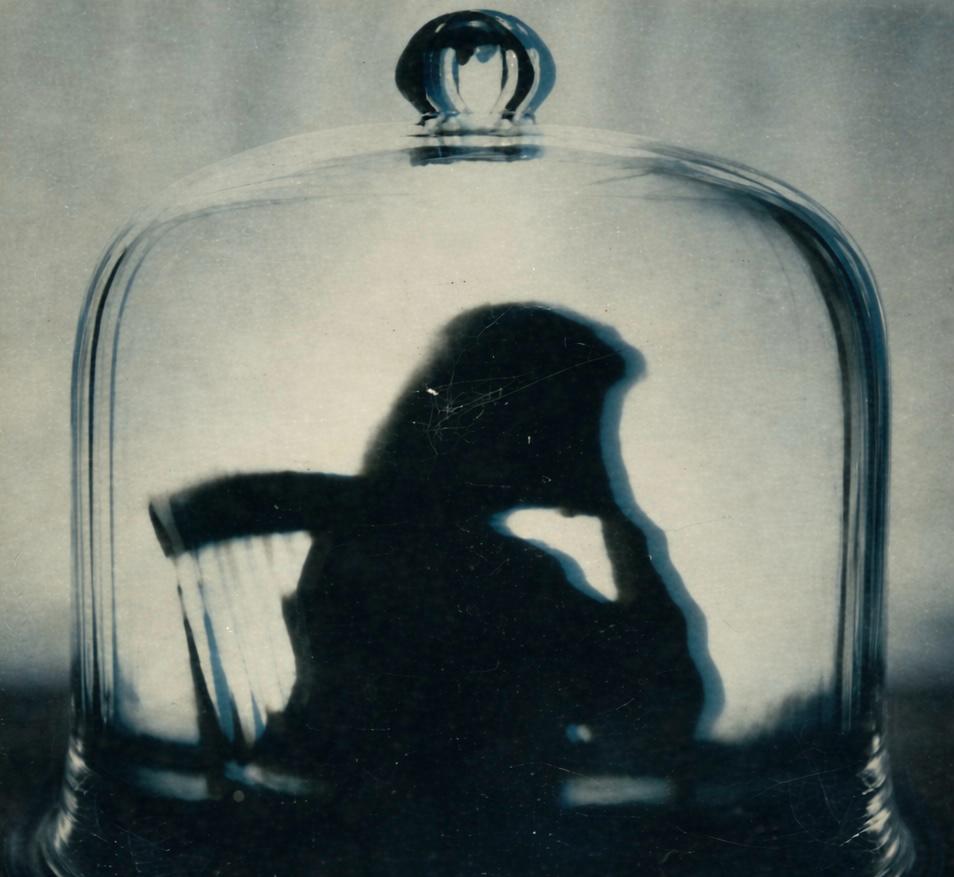

To the person in the bell jar… the world is itself the bad dream.

The Bell Jar, p227.

In The Bell Jar, readers are confronted by a young woman’s struggle with her mental health, which spirals into illness and an unnerving fixation on suicide. The book is a roman à clef which is believed to mirror Plath’s own experience with clinical depression. It is written in the first person, and this makes Esther’s depression palpable, particularly due to her dry, unemotional tone, which signifies the detachment Esther felt from everything happening around her. However, there are subtle shifts in tone throughout the novel, which some readers find to make Esther annoying and self–absorbed. For instance, she recalls a night of drinking with her friend, Doreen, on which she later had to return to her hotel alone, walking forty–three by five blocks in the humid summer air. Unlike Doreen, she had not found a suitable man to spend the night with, and, remembering how she had skulked around her hotel room afterwards, she muses, “The silence depressed me. It was not the silence of silence. It was my own silence.” Her insistence on having experienced a silence unlike anyone else’s reflects the tendency for depression to create a kind of ‘tunnel vision’ for the individuals experiencing it. It is known to create a highly individualistic state of mind where people struggle to see beyond their current negative situation, focusing narrowly on their own problems and fixating on their flaws.

Studies show that clinical depression can not only affect the mind’s response to the world, but can also impact people’s eyesight, to a point where they see colours in paler shades, and begin to lose their peripheral vision. In Esther’s case, she understands her life is the envy of thousands of other college girls, a life that is, on paper, objectively decent. She gets to live in a hotel in New York, working for a magazine and meeting fancy writers and attending fancy luncheons and buying black patent leather shoes and receiving gifts from magazines and beauty companies, and yet she is numb to the entire experience.

Very early in the novel, she states, “I was supposed to be having the time of my life.” Despite her self–awareness, and the knowledge that her life could be worse, she continues to spiral when she receives a rejection letter from a creative writing course she had applied to. This illustrates how, no matter what she does, she feels like she is destined for hopelessness, like her life is shrouded in hues of sepia and charcoal, while the world rushes past her in dewy technicolour.

In other words, she feels trapped and isolated under a suffocating glass dome. This metaphor, of a woman trapped in a bell jar, symbolises Esther’s severe depression and disconnection from the world, like a specimen observed but unable to breathe or truly live. No matter where Esther goes, or what treatments she undertakes, she feels she will forever be trapped under the same hopeless circumstances, secluded in her bell jar, stewing in her own sour air. Even towards the end of the novel, when Esther begins to improve and her doctors consider discharging her, she worries about her bell jar descending on her again, because she sees it as something suspended overhead, ready to drop and engulf her once more. Rather than being merely annoying, the construction of Esther’s character depicts how isolating depression can be, and how it makes individuals brood over themselves, perceiving their life as hopeless, and their existence as a burden on the people around them.

The central metaphor of The Bell Jar calls to memory, Jude from A Little Life, another character whose life is riddled with depression and suicidal tendencies. Jude likens his life to “the axiom of equality.” Granted, its logical foundations are shaky, the mathematical axiom states that any object is identical to itself, i.e. x=x. Jude endures a horrific amount of abuse as a child, and this creates feelings of worthlessness that follow him into his adulthood, where he believes that no matter how successful of a lawyer he is, he will always be the same Jude St Francis who is troubled and undeserving of love. Despite the love that Jude gets from his friends and family, his mind chooses to focus on the people that hurt him, and on the reasons why he feels ‘spoiled,’ ‘dirty,’ and ‘unclean.’ The author of A Little Life seems to share the same thinking as Sylvia Plath, that sometimes, life is not the answer. In an interview with Electric Lit, Yanagihara states,

I don’t believe in it—talk therapy, I should specify—myself. One of the things that makes me most suspicious about the field is its insistence that life is always the answer. Every other medical specialty devoted to the care of the seriously ill recognizes that at some point, the doctor’s job is to help the patient die; that there are points at which death is preferable to life … almost every doctor of the critically sick understands the patient’s right to refuse treatment, to choose death over life. But psychology, and psychiatry, insists that life is the meaning of life, so to speak; that if one can’t be repaired, one can at least find a way to stay alive, to keep growing older.

After reading A Little Life, I remain unconvinced by Yanagihara. The story is so contrived that one can almost see the author torturing Jude like a cartoon satan, raking his sizzling body over the coals, or like the biblical god, inflicting the most gruesome pain on Lazarus just to prove a point. The Bell Jar is more tangible, more real, because it relies less on grand displays of suffering to depict depression. Regardless, both books raise haunting questions about life, and whether suicide can be viewed as the ultimate exercise of one’s agency.

Some humans are more human than others: Racism in The Bell Jar

I rose from the table, passing around to the side where the nurse couldn’t see me below the waist, and behind the negro, who was clearing the dirty plates. I drew my foot back and gave him a sharp, hard kick on the calf of the leg. The negro leapt away with a yelp and rolled his eyes at me.

The Bell Jar, p175.

Reading the classics as a Black person often feels like sinking one’s teeth into a warm slice of banana bread, and then having to spit bits of eggshell onto a napkin, eyeing each slice suspiciously before daring to have another bite. Esther Greenwood’s racism took me off–guard. She is a character in a book that was published in 1963, the same year that Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream,” speech, demanding an end to segregation and racial discrimination. Sylvia Plath’s contemporaries included nonwhite authors such as James Baldwin, and yet neither Sylvia nor her editors were conscious enough to reconsider the racist content in this book.

Esther’s feelings of ugliness and otherness are expressed using vicious comparisons to nonwhite people. After a night of drinking, Esther describes her reflection as, “a big, smudgy-eyed Chinese woman staring idiotically in my face.” After another night out where she gets assaulted by a man, Esther’s face in the mirror looks like “a sick Indian.” When she gets institutionalised, she decides that she hates the only Black employee at the institution. Describing him like a minstrel character who gawps at her with big, rolling eyes, she physically assaults him, kicking him in the calf and spitting, “That’s what you get.”

The internet is divided on what this means for Plath’s writing. It is unclear whether Esther Greenwood’s views on race are Sylvia Plath’s as well. On one hand, this kind of content is to be expected from a book written by Plath, as she was a product of her time. This interpretation of the racist content holds up when one considers that the author was a middle–class White woman in elite academic spaces, who grew up at the height of Jim Crow and probably did not interact with many Black people herself. This, of course, does not excuse her. It merely suggests that, to this poet, people of other races were like exotic birds, stones or even twigs, objects that were only good enough to be similes or metaphors, not whole enough to be human in their own right. For Plath, comparing Esther to people whose lives were imbued with suffering, injustice and inequality, must have been the humiliation that she felt best articulated her troubled state of mind.

On the other hand, her most ardent defenders claim that although The Bell Jar is based on Plath’s life, Esther is a separate person from Sylvia, and does not share her views. A reddit user claims that Esther was meant to be a “a deranged girl going through a crisis of the mind—and this was done through [invoking] a twisted perspective (of others, and the self).” The user includes a quote that is attributed to an essay Plath wrote in 1947, before the socially progressive movements of the 1960s.

“There may come a time when our descendants laugh at our cruel, thoughtless prosecution of different racial groups. Yes, we may wonder how intelligent people could murder ‘witches,’ but how similar are the race riots and skirmishes of today!”

It is difficult and uncomfortable to read books with casually racist characters. Could it have been the author’s intention to depict a privileged white woman losing her mind and demeaning people of other races? Although it is comforting to imagine Sylvia Plath fuming at her desk while writing this story, muttering, “don’t people see how stupid racism is,” the answer to this question remains unclear. The anti–semitic content of her unabridged journals lends no hope. Ultimately, reading The Bell Jar as a Black African person, despite the beautiful prose and the relatable fig tree analogy, leaves a sour taste in the mouth, and leaves one wondering why the racial undertones of Sylvia Plath’s work are not talked about more.

Conclusion

All in all, The Bell Jar is a solid work of fiction, and it is clear why the book has stood the test of time. Plath’s prose is silky and poetic, such that some pages of my paperback copy have more sentences underlined, than those that are not. The racial insensitivity and the harrowing depiction of mental decline still make for uncomfortable reading, so my rating of the book is four stars. One was deducted for racism.

Leave a comment